“Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure” in Europe

Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  October 11, 2022

October 11, 2022  Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  October 11, 2022

October 11, 2022 As the northern hemisphere faces an uncertain winter, many Europeans have started to turn their attention to the quality of their infrastructure. For this month’s newsletter, Holocene is focusing on Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure in Europe. More specifically, we focus on the target of the development of sustainable, resilient, and inclusive infrastructure. To measure this, we rely on the indicator of the rate of rural populations living within 2km with access to all-season roads.

Country roads, take me home

On the face of it, Europe is enjoying a comfortable average rate of 89%. While this is admirable, the remaining 11% masks two deep concerns. The first being the divergence in rates between countries; Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, and Italy all have rates of 99%, whereas Azerbaijan and Cyprus boast rates of 64% and 45% respectively.

The second concern is the sheer amount of people this missing 11% represents. On a continental level (excluding Russia), this would equal 28.9 million people; almost as much as the population of the Netherlands and Belgium combined.

In the past 100 years, Europe has seen a remarkable transformation of its infrastructure marked by two seminal events: the Marshall Plan and the fall of the Soviet Union.

Keynesian Economics + Europe in Tatters = The Marshall Plan

Following the end of WWII in 1945, Europe was falling apart – literally and figuratively. After 6 years of brutal war, the continent was in desperate need of financial assistance to help it rebuild; assistance which the U.S. was well positioned to supply. Over the course of 4 years from 1948 through 1952, the U.S. sent over $13 billion in aid ($115 billion in 2021 terms) to the nations of Europe to help them rebuild. This injection of capital proved to be transformative for the recipient nations and set them on a path for a rapid economic recovery. While not limited exclusively to all-season roads for rural populations, the plan serves as a proxy for the rapid transformation that Europe’s infrastructure experienced during this period.

The second major development of the 20th century was the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. In the years following the collapse, many ex-Soviet nations with less developed infrastructure began a journey of ‘catching up’ with the rest of Europe, especially after joining the EU. As illustrated in Figure 1, many of the nations in the post-Soviet bloc still lag behind their Western counterparts, though progress is still being made.

Over the past 20 years, there have been two major shocks that had a seismic impact on infrastructure within Europe in the 21st century; neither of which are the pandemic. The two great shocks are the Great Recession and the war in Ukraine.

“You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take. – Wayne Gretzky” – Michael Scott

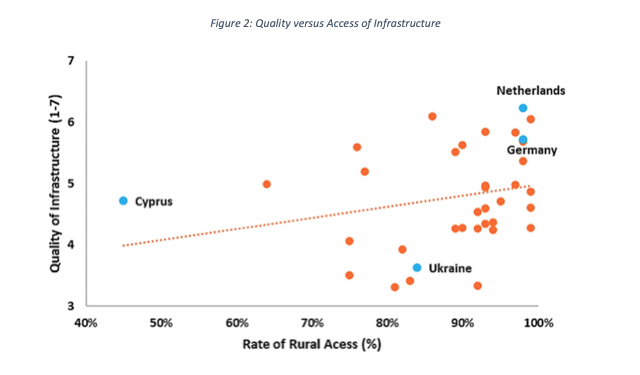

One unintended consequence of the Great Recession was how during the recovery European governments prioritised austerity over increased investments to spur the economy. While some economists argue that this belt-tightening extended the slow recovery, it also led to years of under investment in infrastructure. This lack of investment has been seen all over the continent, whether it be crumbling roads, bridges, or tunnels that are in dire need of maintenance. As highlighted in Figure 2, Holocene believes quality is as important as quantity.

Look at Germany, Europe’s largest economy and the engine of the continent. While it scores quite well at 98% on the Rural Access Index and 5.7 in overall quality of infrastructure, both measured by the World Bank, (7 being the highest), these scores mask a dire need to upgrade and repair. According to estimates by KFW, municipalities across the country are facing an investment backlog of €149bn ($172bn).

War in Ukraine

Now turning to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, two facts stand out. First, even before being invaded, Ukraine was severely lacking in both the quality of its core infrastructure as well as the access for those living in rural areas. Second, given the destruction that war brings, much of Ukraine has been flattened both in urban and rural settings. According to estimates by DWS, the cost to rebuild Ukraine may be $349 billion; $249 billion more than all of Europe received under the Marshall Plan (when converting the original aid in 2021 terms).

One approach to supporting the development and rollout of infrastructure across a continent is to throw money at the problem. Given the current runaway inflation the global economy is experiencing, that solution does not appear to be in vogue for 2022 or 2023. Instead, we focus on how to effectively identify where investment is needed the most.

Over the years, the ability to measure the rate of rural population living within 2km of an all-season road has increased by leaps and bounds. When the Rural Access Index (RAI) was first developed in 2006, the target was measured by having statisticians travel around the countryside and relying on a mix of household questionnaires.

Then in 2016, the RAI entered the digital realm with the help of UKaid, in partnership with the World Bank, and developed ReCap. The result was a modern solution using three levels of geographic information system (GIS): where people live, where roads exist, and if the roads have all-season access.

Building off this success, there have been numerous developments including space-based technologies being utilised to assist policymakers to identify new areas for development as well as old areas in need of repair. Some of the benefits of using space-based technologies include the ability to affordably and reliably map difficult to reach areas, the ability to monitor developments in real-time, and the ability to automate the processes; processes that would be otherwise manually conducted and expensive.

A final consideration is one that has been touched upon above, the question of quality. Not only does Europe need to continue investing in its rural infrastructure, but it will have to ensure that they are fit for purpose in a changing world.

This past year has brought the issue to stark relief on the continent with a host of climate challenges: droughts that scorch the land, floods that damage towns, or heat waves that distort roads. Not only in the years ahead, but the months ahead, countries across Europe will have to begin designing their roads differently to sufficiently take climate into consideration. After all, an all-season road is not of much use if it is damaged or under water.

If you would like to learn more about our capital raising solutions, please email info@holoceneic.com.