“Affordable and Clean Energy” in Africa

Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  August 10, 2022

August 10, 2022  Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  August 10, 2022

August 10, 2022 Each month, Holocene covers a United Nations Global Goal, a continent, and a target on a rotational basis for our Insights Briefings. (If you missed previous editions, you can find them here.)

Addressing access to energy in Africa is critical for achieving Global Goal 7: of the nearly 800 million people in the world without access to energy, almost 600 million of them are in Africa. From a macroeconomic perspective, 6% of GDP is lost per year due to a combination of power outages and electrical inefficiencies. On an individual level, from dirty cooking methods, to lack of properly treated water and the inability to read at night or study remotely, it is clear that without reliable access to electricity, you are essentially cut off from the benefits of the modern world.

Africa is simultaneously blessed with an abundance of energy resources yet critically lacks access to modern energy solutions. The result is a situation where despite resources being exported to help electrify the world, nearly 600 million Africans still had no access to any form of electricity as of 2021.

To put it into perspective another way, Africa as a continent generated 854 terawatt-hours (TWH) of electricity in 2019 while the U.S. generated 4,461 TWH. On an individual level, the average African only consumed 200 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per year, versus the EU where it was over 1,500 kWh. Taken at face value, these numbers are shocking. What they also represent is that for many in Africa, not only are so many people unconnected to the grid, but for those that are, the amount or quality of the energy is lacking.

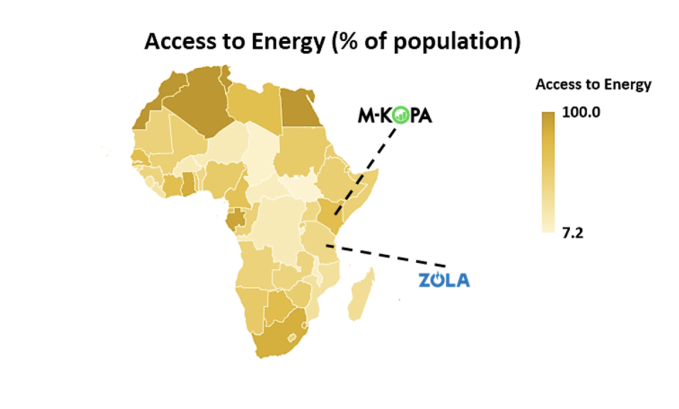

In northern Africa, you have countries such as Egypt and many of its North African peers reaching 100% electricity access. Whereas in Sub-Saharan Africa, the rate can drop to as low as 7.2% in South Sudan or 11.1% in Chad.

While each country has its own set of unique circumstances, a few common factors either supported, or hindered their past electrification developments:

From 2010-2020, 467 million people finally gained access to electricity. Unfortunately, at the current rate of progress, there will still be 679 million people without access to electricity by 2030. Another worrying concern is that for the people that do remain connected to the grid, they will become progressively harder and more expensive to serve as investments generally target those that are easiest to connect first.

Within the African context, the rate at which people were gaining access to electricity on an annual basis tripled from 8 million in 2000, to 24 million in 2013. One of the initiatives supporting this growth was the increased reliance on decentralised and renewables-based solutions. As of 2019, 51 million people on the continent had access to off-grid solar solutions. Sadly, this trend began to reverse due to the pandemic. In 2020, the number of people in Africa without access to electricity increased for the first time rising to 590 million people, 3% more than before the pandemic. This was due to the economic hardships suffered by those at the very bottom rungs of the economic ladder whose purchasing power declined drastically.

In the immediate years ahead, there are four risks threatening this goal in the continent: two global factors, and two local factors.

Globally, there are two threats: the looming energy crisis due to the war in Ukraine and the surge of global inflation. The resulting uncertainty in global markets will cause African nations to fall further down the pecking order of nations receiving necessary energy imports. The rise of inflation will hit those at the bottom the hardest just as the pandemic did.

Locally, it is expected that the rate of electricity access will slow down in the coming years as those that are added to the grid become progressively more expensive to serve. A second risk is demographics. As the population of Africa swells, there is a risk that ongoing efforts to connect people will not only fail to meet the targets of the Global Goals but begin to backslide if it fails to keep up with a rising population.

To achieve full access to electricity by 2030, 100 million people need to be connected to the grid every single year globally. In the African context, it would require connecting 85 million people a year.

Given the historical obstacles of securing funding in the region, relying on $35 billion per year is wishful thinking. Instead of focussing on the macro (problems), at Holocene we like to focus on the micro (solutions). One such solution involves rethinking something much less exciting than solar panels or wind turbines: the grid.

Often taken for granted, the grid and its stability are what ensures continual access to energy without interruption. According to IEA estimates on reaching net zero emissions by 2050, around 30 million people a year in Africa would have to secure electricity through decentralised solutions such as mini-grids with renewables powering them by 90%. The benefit of a decentralised grid lies in the ability to build the facilities where the people live, a massive gain given the rate of people living in rural communities in the continent. From 2030 onwards, once a sufficient critical mass has been reached, the next phase is connecting the mini grids together, almost like a spider’s web. This would allow for power to be generated to meet the demands of the local communities requiring less capital and supporting their economic development.