“Clean Water and Sanitation” in Oceania

Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  July 11, 2022

July 11, 2022  Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  July 11, 2022

July 11, 2022 For the sixth instalment of Holocene’s Global Goals Briefings, we examine “Clean Water and Sanitation” in Oceania – the continent of islands and archipelagos. Specifically, this briefing examines the first target of “safe and affordable drinking water” measured by the proportion of the population using safely managed drinking water services.

There are 3 Canada’s worth of people with zero access to any water services.

Access to water has been recognised as a human right by the United Nations since 2010 and reflects the fundamental nature that it plays in every person’s life. Unfortunately, this universal human right is far from universal in its application. Currently, nearly 2 billion people live without access to basic services where access to water is under 15 minutes away. Of that group, 122 million people collect their water from untreated surface water such as lakes, ponds, rivers or streams. That’s roughly the equivalent of everyone in Australia, Canada, Chile, and Poland all having to drink untreated surface water on a daily basis.

The human consequences of the lack of safe and accessible drinking water are stark. Each year, an estimated 830,000 people die from unsafe drinking water leading to diarrhea. This is all the more tragic given these deaths were preventable.

In the context of Oceania, the lack of safely managed water services is even more pronounced where only 57% of the population have access to basic drinking water facilities, well below the global average of 78%. This low rate is due to a combination of 6 factors:

The result is a region with unique challenges that will require entirely new solutions to address them.

Water comes in 3 states: liquids, solid, and gas. Also coming in 3 is what is known as the ‘hydrologic cycle’ and how water is exchanged throughout the Earth: evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. Through this constant process of transformation through states and phases, the Earth has successfully managed and regulated the flow of water since it first appeared. Put another way, the quantity of water on the planet has been almost fixed since it first arrived on the Earth nearly 4 billion years ago.

The story of humanity, and its relationship with water go back considerably less: only 10,000 years, since when humans decided to build permanent dwellings, generally near a source of water. Now, as the climate changes, what we are witnessing is not water that has become uncontrollable and interfering with our way of living, but it is doing what it has always done: adapt regardless of humanity’s existence.

There are many methods for humans to produce and distribute clean drinking water in a world where the amount of water is finite. Thus, the question of how to deal with water is not a technical question but a political and philosophical one. For the purposes of this briefing, the argument comes down to “Right to Access” versus “Duty to Consume Responsibly and Efficiently”.

Right to Access – People First

The argument here is simple: people have a right to safe and clean water, and governments have obligations to address these rights. Part of these obligations include mandates for the services to be readily “accessible”, as well as “affordable”. Unfortunately, there is no agreement on what affordable and accessible mean in this context. The result is a situation where water is highly accessible at very low cost across the rich world and leading to rapid depletion of local water resources. Whereas in the developing world, water is not only scarce, but also unaffordable and inaccessible.

Duty to Consume Responsibly and Efficiently – Resource First

The second side of the argument – Duty to Consume Responsibly and Efficiently – is rooted in the understanding that water on the Earth is finite. Rather than a duty to provide as much water as possible, the key is to focus on balance. What would matter more is to ensure that all consumers – and corporates – take decisions that would increase the efficiency in their consumption to reduce the total demands on the water supply. Solutions tackling this could include smart water metres, rain water catching facilities, and introducing wide varieties of plants instead of water hungry variants.

Ultimately, at Holocene, we believe the key is to focus on initiatives that not only address the people lacking the water, but also on solutions to do so responsibly and efficiently to avoid mistakes made in the developed world.

2 billion too many.

While the world has made progress on achieving its target of access to water, it has been very slow, increasing by only 4% total over the past 5 years. If the world is to have any shot of reaching universal access to water by 2030, the rate of progress must more than triple in the coming decade. Unfortunately, even if progress is made, it is a race against the clock. As of today, there are already over 2 billion people that live in water-stressed countries and is expected to rise dramatically because of climate change and demographic shifts. This is all the more concerning when considering groundwater levels across the world have been depleting at a record pace.

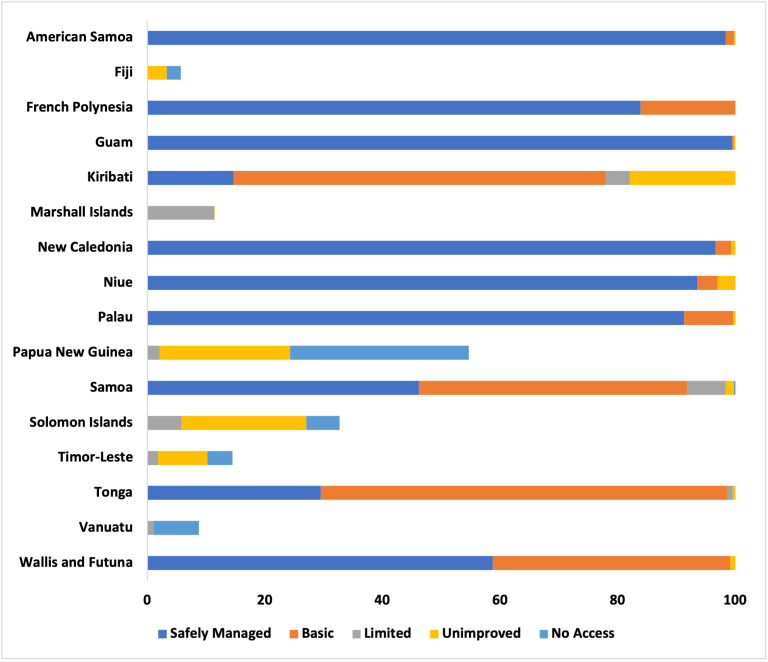

In Oceania (minus Australia and New Zealand), while progress has been made, it has not kept up with the rate of urbanisation. This has led to a situation where not only the rural populations have little access to safe and reliable water, but many people living in the cities are experiencing water insecurity as well. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the different levels of water access in the region.

Table 1: Proportion of Water Access by country. (WHO/ UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation)

To achieve the goals of universal access to safe drinking water, it will require a combination of both respecting the right to water, as well as encouraging more responsible consumption of water. The solutions will have to be flexible, future proofed, and financially affordable; flexible in balancing the needs of outcomes versus efficiency; future proofed against a changing climate and finally, financially affordable given the low incomes of the residents in spite of the high up-front costs.

An example of one such solution combining all 3 was on Fiji’s Kia Island. Following Cyclone Yasa in 2020, the island’s fresh water supply system was damaged beyond repair. This then led the Fiji government to turn to the Pacific community to help drill two new boreholes with the capacity to store 2,000L of freshwater a day for the local community. For only $USD 5 per person, villagers were able to run taps straight to their homes.

To ensure that safe and affordable drinking water becomes a reality across Oceania in 2030, it will take many initiatives like the one in Yasa.

Below are two companies in the region doing good work in the space to address safe and affordable drinking water:

Headquartered in Australia, Wallaby Water provides clean and affordable drinking water for consumers in recyclable aluminium cans instead of single use plastic bottles. Since their launch in 2019, they have replaced over 2 million plastic bottles.

Also headquartered in Australia, VAPAR is a cloud platform solution for pipe asset management. Its software helps its customers maintain and repair their critical infrastructure through the use of CCTV footage leading to significant savings.