“Zero Hunger” in Asia

Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  March 9, 2022

March 9, 2022  Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  March 9, 2022

March 9, 2022 This month’s edition examines the United Nations’ (UN) second Global Goal “Zero Hunger” in Asia. Specifically, this briefing examines the first target of universal access to safe and nutritious food by 2030.

For those of you that missed out on last month’s edition focussing on “No Poverty” in Africa, you can find it here.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), food insecurity is defined as lacking ‘secure access to sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food for normal growth and development and an active healthy life’. For the purposes of this briefing, we use the rate of undernourishment as the main indicator of hunger. With that in mind, in 2020, the UN estimated that 2.3 billion people representing 30% of the global population, lacked year-round access to adequate food. 30% of the global population is not only sobering; it is inexcusable.

Our relationship with and access to food has long been a defining characteristic throughout the course of history. Human history can be divided by three Agricultural Revolutions:

The Green Revolution was an especially important achievement as it brought agriculture into the modern age through the adoption of the latest technologies applying modern science to farming, the use of high yielding varieties of seeds, the use of fertilisers, and the consolidation of land. Taken together, the Green Revolution had managed to increase farm yields by 44% between 1965 through 2010.

Remarkably, the impact does not end there, with evidence suggesting the Green Revolution reduced rates of hunger for millions, raised incomes, reduced poverty, lowered greenhouse gas emissions via more efficient farming methods, and led to a decline in infant mortality rates.

Despite the success of the previous decades, hunger and under-nutrition have been on the rise since 2015 due to a combination of pandemics, pests, and politics.

With COVID-19 running loose and bringing the global economy to a standstill, people in developed and developing countries suffered alike. The inability to work, send remittances home, the reduction of purchasing power, and the halting of global supply chains all directly impacted the world’s most vulnerable populations.

In 2020, as the world was collectively battling a new plague, the global south was dealing with an ancient variety: locusts. Swaths of Africa, South Asia, and even South America were ravaged by swarms of locusts impacting over 2.25m hectares of land and left tens of millions of people facing severely acute food insecurity.

As bad as 2020 and 2021 were, 2022 is proving to be even more significant due to the third enemy of food security: politics. The way politics impacts food security can be divided into demand versus supply.

In 2021, after nearly 20 years of war, the Americans and their allies withdrew their forces as the Taliban took control of the country. Since the unilateral withdrawal of western forces, the humanitarian situation of Afghanistan has rapidly declined. With international aid coming to a halt (which accounted for 40% of GDP) for fear of supporting the Taliban regime, more than 23 million Afghans face acute hunger with the UNDP estimating that 97% of the population will ‘plunge’ into poverty in 2022.

To be clear, this is a political problem. With the US Government locking up billions of dollars belonging to the Afghan Central Bank and stringent sanctions eliminating all business interest in the country, millions of Afghans are left without a functioning economy and are starving as a result.

On 24 February 2022, Russian forces invaded Ukraine, of which the full range of consequences are impossible to determine at this time. One major risk is the impact on the global supply of wheat because Russia and Ukraine are the world’s third and seventh largest producers respectively and account for 30% of global wheat exports. As the war rages on, it is inevitable that the supply of wheat, a staple food for millions of people around the world, will be devastated. Since the start of the invasion, the price of wheat has leapt from US$873 per bushel on February 23, to US $1,340 – an increase of 53%. The last time wheat prices increased that dramatically, the world witnessed the Arab Spring less than a year later.

Two Nobel Laureates earned their prizes for their work related to food and food systems. The first is Norman Borlaug, the “Father of the Green Revolution” who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970. His work to develop high-yielding varieties of cereal grains, along with the application of modern farming techniques is credited with saving over a billion people from starvation.

The second is Amartya Sen who received the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences (Nobel Prize in Economics) for his research on fundamental problems in welfare economics and poverty. Inspired by his experiences growing up in India, Sen focussed on the Bengal famine and noted that while food production was lower than the previous year, it was actually higher than non-famine years. The cause of the famine, which killed 2-3 million people, was due to a cocktail of factors including an urban economic book that raised food prices, declining wages, unemployment, and poor food distribution.

As highlighted above, the causes and solutions of hunger are multi-faceted. On a systems level, it is not only the production of food. There are millions of jobs involved, revenue streams, large supportive infrastructure and important links connecting rural with urban populations. At its simplest level, there are two key pillars: policy, and technological development.

Under agricultural technology specifically, there are five main sectors: Food & Beverage, Agtech, Restaurant Tech, Food & Beverage Delivery, and Alcohol Tech. Of the five, Agtech is most aligned with addressing the target of universal access to safe and nutritious food by 2030. As a sector, it saw its funding increase from $1.3B in Q2 2020 to $2.1B in Q2 2021.

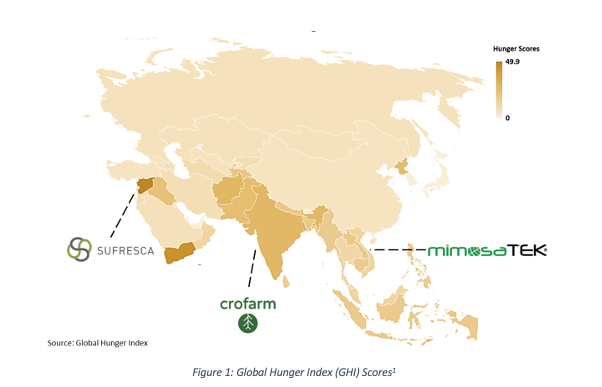

In our research at HIC, we identified three interesting companies based in Asia looking to address zero hunger.

Based in Israel, Surfresca has raised over $7M to develop bio-edible coatings for fruits and vegetables. The benefit of their solution is the ability to prolong the shelf life of produce to reduce waste and help support a plastic free world.

Backed by Pravega Ventures and based in India, Crofarm developed a mobile app platform supply chain system that connects farmers to consumers to reduce food waste.

Founded in 2014 in Vietnam, MimosaTEK developed a cloud-based system allowing farmers to control and manage their farms with sensors to monitor the environment, crop progression, and remote irrigation execution. The goal was to allow previously manual labouring farmers to tap into modern agricultural technological solutions.

These three companies are just a sample of the great work happening in this space and we at HIC will be keeping an eye on this in the months to come.