“Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions” in North America

Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  October 10, 2023

October 10, 2023  Adam MacRae

Adam MacRae  October 10, 2023

October 10, 2023 On October 03, 2023, the United Nations Security Council finally agreed to send peacekeepers to Haiti to quell rampant gang violence that has brought the country to its knees. In Mexico, a recent paper concluded that if the nation’s narco cartels were ‘formal employers’, it would be the fifth largest employer in the country. In the United States, as of September 30, there were 487 mass shootings; roughly 1.7 mass shootings per day.

For this month’s briefing, we are going to address one of the thornier topics thus far. The 16th Global Goal of “Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions”, is understood to be not only a goal in of itself, but also an enabler for the other 16 Goals. Within this complex and controversial theme, our focus currently is on “reducing violence everywhere” as measured by the number of intentional homicides per 100,000 people in North America.

As we turn our attention back to the rate of intentional homicides, let’s start big.

Global

Regional

To start, we can determine what it is not:

Rather, intentional homicide is “the unlawful death inflicted upon a person with the intent to cause death or serious injury”. With this definition in mind and looking at the numbers, you’re much more likely to be killed by someone you know.

To have a birds-eye view of the situation, we’ve examined intentional homicide on three dimensions: economic, gender, and geography/climate.

More Money, More Problems?

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), regions that experience high levels of economic disparity and inequality are four times more likely to experience homicides. While not the only factor, it is an important one to bear in mind and a useful shorthand as it is easily quantifiable, and measurable over time.

In terms of measuring economic disparity, the simplest measure is the Gini coefficient which measures the inequality of income distribution with a score of 0-1, 0 representing perfect equality and 1 representing perfect inequality. Another way of thinking of that score would be 0 meaning every person in the country has the exact same amount of money, while 1 would mean 1 person had all the money in the country.

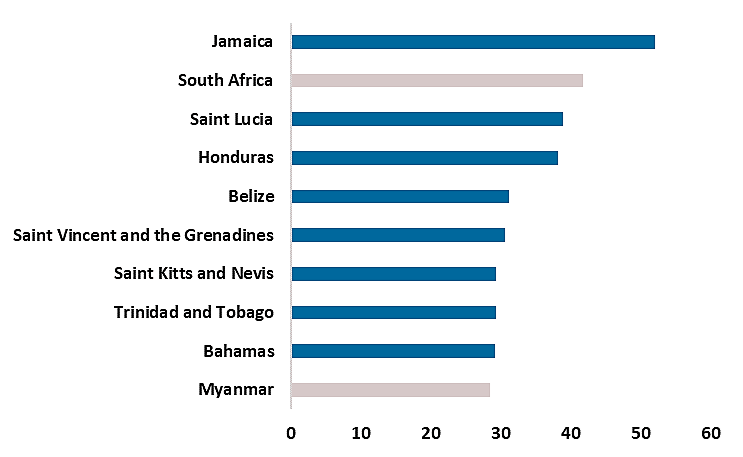

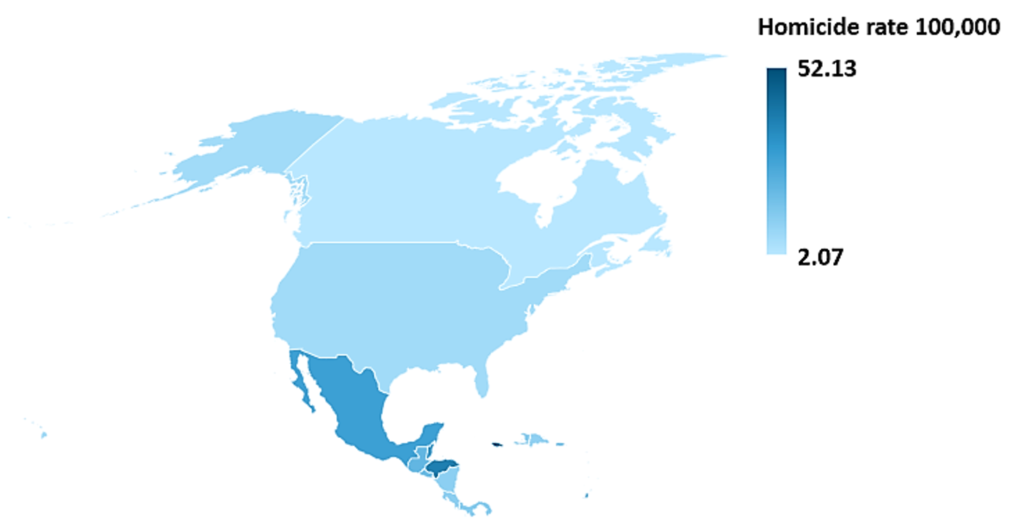

In the North American context, we find that 12 countries have a score of 0.38 or higher. This does not sound like much, but when we recall the findings of the UNODC, it partially explains why North America and Latin America experience such high rates of homicide. Compared that with Canada which comes in at 30.3 whereas Norway and Finland are comfortably in the 20s. Vast differences are hidden in these numbers. This is all the more striking when looking at Figure 2 and seeing that not only does Canada enjoy the lowest levels of income inequality, but also the lowest levels of homicide rates in North America at 2.07%.

A second dimension that deserves much attention is the role of gender. 81% of all victims of homicide are men. This is usually a crime on men perpetrated by men and the result of aggressive circumstances outside of the home. This is a genuine male epidemic.

If addressed properly, actions taken today could save the lives of tens of thousands of (generally) young men every year; men that could have otherwise had the chance to lead productive lives in society. This tragic loss of life leads to a great number of fathers and sons that have been robbed of the prime of their lives.

Then there is the other 19% that women make up, of which, 56% are killed by intimate partners or family members. A home should be a place of safety and security. For many women, it could be the most dangerous place in the world.A final consideration is that of a changing climate. As we have addressed at length in previous briefings, climate change is not something we have to worry about in the future – it’s already here.

Over the last 60 years, over 40% of all conflicts were in some way related to natural resources. Humanity’s reliance on the natural world and the changing nature of climate is complex, global, and interconnected. On a macro level, climate change has already led to significant political unrest with the Arab spring in part tied to poor grain harvests leading up to the revolutions.

On a more local level, when individuals are caught in a perceived zero-sum situation competing over the same local natural resource, tempers will inevitably flare; this is especially true in rural areas where farmers and herders are often at odds.

In the years ahead, this will become even more of a priority area for policymakers. With the changing climate, some think tanks estimate that up to 1.2 billion people may have to give up their homes in search of a better life elsewhere and further away from the equator in effect becoming climate refugees. This could then potentially lead to an uptick in homicides in the future if not properly managed.When looking back at the 3 dimensions above, a few solutions present themselves. Below, they are broken down into short, medium, and long-term solutions.

Short-term.

As the majority of intentional homicides against women occur in the home or by people they know, more money and support needs to go into programs designed specifically for supporting women. This can include a combination of women-only support shelters, investing in social workers, hotlines for women to privately reach out to, or even as simply as taking their concerns seriously. These programs are often some of the least expensive and can start saving women in dangerous circumstances as soon as today.

Medium-term

The second is targeting men and promoting economic opportunities. Many men find themselves, especially in North America, drawn to gangs and other dangerous circumstances because of the lack of alternatives in the job market. For example, a recent study in Mexico showed that if efforts were directed towards targeting potential future recruits to the cartels and providing them stable jobs, the numbers operating within cartels would fall by over 100,000 by 2027. Less disenfranchised men on the streets will inevitably lead to less men-on-men intentional homicides.

Long-term

Potentially the most important policy lever is a fairer system of progressive taxation. However, there are two downsides to this solution. One, taxes are generally unpopular. Two, the benefits will only be seen in the decades ahead. However, given the strong relationship between income inequality and homicides, policymakers would be turning their backs on a safer future if they were to not seriously consider the option.

Finally, as the climate continues to change in the years to come, it will be important to engage with people in the most vulnerable areas to support them now. Actions taken today, such as managing resources more responsibly or building more adaptive infrastructure will prevent long-term suffering.

If you would like to get in touch with Holocene and learn more about our geopolitical risk capabilities, contact us at info@holoceneic.com